Heading Color Test

December 3rd, 2010Behavior Wizard

December 3rd, 2010The Behavior Wizard is a method for matching target behaviors with solutions for achieving those behaviors. It is a systematic way of thinking about behavior change. The Behavior Wizard expands the Behavior Grid and the Behavior Model by combining our best work into one easy-to-use solution.

Fogg Behavior Grid – 15 Ways Behavior Can Change

The Fogg Behavior Grid outlines 15 types of behavior as defined by BJ Fogg. The grid describes the ways behavior can change. Its purpose is to help people think more clearly about behavior change.

Each of the 15 behaviors types uses different psychology strategies and persuasive techniques. For example, the methods for persuading people to buy a book online (BlueDot Behavior) are different than getting people to quit smoking forever (BlackPath Behavior).

With this framework, people can refer to specific behaviors like a “PurpleSpan Behavior” or a “GrayPath Behavior.” For example one might say, “The Google Power meter focuses on a GrayPath behavior.” These new terms give precision.

But this innovation goes beyond identifying the 15 types of behavior change and giving them clear names. The model also propose that each behavior type has its own psychology. And this has practical value: Once you know how to achieve a GrayPath Behavior, you can use a similar strategy to achieve other GrayPath Behaviors (for example, getting people to watch less TV). In this way, the Behavior Grid can help designers and researchers work more effectively.

Fogg Behavior Model – What Causes Behavior Change?

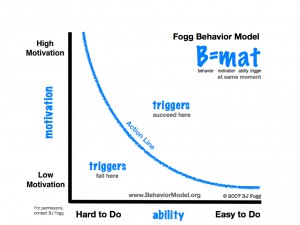

The Fogg Behavior Model shows that three elements must converge at the same moment for a behavior to occur: Motivation, Ability, and Trigger. When a behavior does not occur, at least one of those three elements is missing.

Using the Fogg Behavior Model (FBM) as a guide, designers can identify what stops users from performing behaviors that designers seek. For example, if people are not performing a target behavior, such as rating hotels on a travel web site, the FBM helps designers see what psychological element is lacking.

The FBM also helps academics understand behavior change better. What was once a fuzzy mass of psychological theories now becomes organized and specific – and practical –when viewed through this model.

The Behavior Wizard & Resource Guides

To make this approach to behavior change clearer and more useful, we created the Behavior Wizard and Resource Guides for each of the 15 types of behavior change. Each guide gave more examples, explained relevant theories, and highlighted real-world techniques for achieving the specific behavior type.

We felt that in the past, most designers and researchers guessed at solutions for changing behavior. And frankly we saw that most attempts failed. Rather than guessing at solutions, people who used our Resource Guides had clear guidance. The Behavior Wizard generated these Resource Guides, drawing on the ever-improving content our team created (it was like wikipedia for specific types of behavior change).

UPDATE

The Behavior Guides were created in 2010 and we are no longer updating or selling them.

There is still lots of useful information in these guides. If you’re interested in obtaining a specific guide, please email us (captology@stanford.edu) and let us know in which guide you’re interested and why. We may be able to share a copy with you.

Behavior Wizard Project Team

The following people have contributed their time and energy to this project.

BJ Fogg, Project Director

Jason Hreha, Project Lead

Robin Krieglstein, Web Developer

Kara Chanasyk, UX Designer

Gaj Krishna, Research Specialist

Gaju Bhat

Shuqiao Song

Visit www.behaviorwizard.org to learn more.

Article: Thoughts on Persuasive Technology

December 3rd, 2010by BJ Fogg, Ph.D.

Director, Persuasive Tech Lab at Stanford University

The world of technology has changed dramatically in twenty years. In 1993, I went to Stanford University to study how to automate persuasion. As a doctoral student, working with Cliff Nass and Byron Reeves, I was trained as an experimental psychologist. I had one question I wanted to answer: How could you computerize persuasion? In other words, how could you use the power of computers to change what people believed, how they behaved, and how could this then be applied to improve the world in some way?

The first experimental studies we performed at Stanford were not received very well by outsiders. I remember presenting the results at an academic conference, and at the end, there were 3 reactions: 1) people didn’t believe the data – they thought somehow we had run a flawed experiment; 2) people thought the work was evil, that it was equivalent to creating the atom bomb; or 3) (and this was just a small segment of the audience) they found the work fascinating, and they could see the immense application in the future.

We continued the experiments. As part of the CASA research group at Stanford, I focused exclusively on persuasion, specifically how computers could leverage social dynamics such as group support, personality differences, praise. I explored how those social dynamics could change people’s opinions and, even more importantly, their behaviors.

After we ran a number of experiments, and after these studies were replicated elsewhere, the results were undeniable. Computers could indeed be designed to influence people, to change their thoughts and behaviors. Today, this notion that computers can persuade people is no longer novel. In fact, experiments to show this phenomenon aren’t interesting because we now have thousands of Internet services, applications for mobile phones, experiences and social networks like Facebook, that change our behavior on a daily basis; they influence us. Computing technologies are not only changing us individually, but are changing our culture. So in twenty years, we have come a very long way from computers being seen as machines to store and manipulate and crunch data, to machines that are part of our everyday lives—machines that influence our thoughts and actions, our friendships, and even the relationships between countries.

Today, we are surrounded by persuasive technologies. Everywhere that digital media touches our lives, more and more there is an element of persuasion; a design created by humans and implemented in code to influence what we think, and more and more, what we do. We are surrounded. Persuasive technology is in our living rooms, in our cars. When we communicate with our loved ones online, through Facebook, persuasion is there. When we withdraw money from the bank at the ATM, an element of persuasion may be there. When we purchase a gift online for a birthday, once again, we are being exposed to persuasion. In fact, we carry a persuasive platform, the mobile phone, with us most everywhere we go.

Yes, we’ve come a long way in twenty years; technology has shaped who we are. In fact, I believe the mobile phone is the next step in human evolution, literally. Almost everyone coming into the world will have a mobile phone with them, by their side, for the rest of their lives. We are not just flesh and bones; we are now flesh and bones augmented with technology, and we will live the rest of our lives through technology connections, leveraging the power.

This is the current state of affairs, and it is our future. There is nothing we can do, like it or not, where we can escape persuasive technology. This makes it all the more important to understand what the potentials and pitfalls are for creating machines that influence humans, because in essence that is what we are doing. We are creating machines that control humans and human behavior. On the face of it, this seems a radical, even heretical, notion. It’s notable that not more people have become upset by this prospect. If twenty years ago, I had announced that we would soon be creating machines that control humans, there would have been an uproar. But today, the uproars around Facebook, around Google’s domination, around Apple’s seductive products, are small compared to the actual impact this is having in our lives. Understanding what’s going on today with technology and influence helps us to see the future.

Technology will continue to change. That’s something that makes working in persuasive technology so exciting. Every day, a new development, a new start-up, a new product, something that opens new potentials for persuasive technology; it is never static, always dynamic. It can be daunting to stay current with all the new developments.

But there is a constant in persuasive technology. That constant is human psychology. For thousands of years, we humans have fundamentally been motivated by the same things. We’ve had the same types of mental abilities and so on. Because human psychology is the constant in the world of persuasive technology, the more we learn about what makes humans tick, what motivates us, what capabilities, what weaknesses, what we aspire to, what we fear — the more we learn about human nature, the clearer our understanding of persuasive technology will be.

In my training as an experimental psychologist, I’ve come to appreciate over the years the grounding in human psychology and understanding humans first, and understanding how technology is then a channel for helping humans achieve their goals, for influencing people to do better, for changing organizations, and yes, for transforming the world; for that is, indeed, my hope for persuasive technology and for the innovations in this arena: that we can use the power of digital technologies, we can leverage the scale and speed of social networks to bring about positive changes in relationships, in environmental behavior, and in our health, both at local and global levels.

If I weren’t an optimist about human nature, I would be worried about the future. But I am an optimist. I believe that we humans are fundamentally good. Now that persuasive technology is being put into the hands of millions of people (for example, my mother can start a group on Facebook and influence hundreds or thousands or perhaps millions) the tools for creating these systems are no longer given only to the highly trained or to large companies. More and more everyday people can create websites, can create applications, can reach out, and this is a good thing, I believe, because humans are basically good; because they want to do good things in the world.

By empowering millions of people to create persuasive experiences with technology, we will have thousands, and perhaps millions, of forces working toward the better in the world. And that, I believe, offsets the negative: the power that evil people and corrupt organizations will gain with persuasive technology.

So I encourage you the reader, as you move forward through the pages of this book, that you keep primarily in mind how the potential of the technology can be used to make the world a better place: more peaceful, more prosperous for everyone; how technology can help individuals be happier and be better contributors in their communities. This book explores some important issues of technology and its effect on individuals, our communities, and our culture. It is my hope (as with my classes at Stanford, the work I do in industry) that you will use what you learn in these pages to bring about positive changes in the world, and that you will inspire others to do the same.

Dr. BJ Fogg

Stanford University

November 2010

Persuasive Online Video

December 1st, 2010Persuasive Online Video

Online video is a powerful way to persuade people. The 2008 elections in the U.S. gave a vivid demostration of how YouTube and similar sites could engage people with a persuasive message. In our lab we have studied the elements of persuasive video. Our work, which includes real-world interventions, has shown dramatic results. We expect this area to keep growing especially as we see the emergence of better tools for creating, distributing, and measuring online video.

To create insight on this topic, BJ Fogg organized a Stanford conference to bring experts together. He later created a new course called “Persuasive Online Video,” which was taught in Spring of 2009 with Enrique Allen.

For more information about persuasive online video, please contact us.

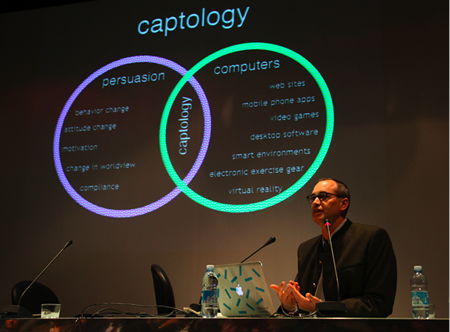

What is Captology?

December 1st, 2010Captology is the study of computers as persuasive technologies. This includes the design, research, ethics and analysis of interactive computing products (computers, mobile phones, websites, wireless technologies, mobile applications, video games, etc.) created for the purpose of changing people’s attitudes or behaviors. BJ Fogg derived the term captology in 1996 from an acronym: Computers As Persuasive Technologies = CAPT.

Where Persuasion and Computers Intersect

The field of captology and persuasive technology is growing quickly. Every day more computing products, including websites and mobile apps, are designed to change what people think and do.

As we see it today, captology isn’t just persuasive web sites or video games to change behaviors. Captology is a way of thinking clearly about target behaviors and how to achieve those goals using technology. Captology is a method with related tools for solving problems. Our frameworks and theories are all about helping people understand and measure what matters.

Captology Resources

People often ask how they can learn more about captology. Here are some things we suggest.

- Review the Resources available on this website.

- Sign up for our free email newsletter.

- Join our Facebook Page and learn about other ways to engage.

- Check out BJ Fogg’s personal website.

We’ve also created some books related to captology:

Paper: Mass Interpersonal Persuasion

November 23rd, 2010A new form of persuasion emerged in 2007: I call it “mass interpersonal persuasion” (MIP). This phenomenon brings together the power of interpersonal persuasion with the reach of mass media. I believe this new way to change attitudes and behavior is the most significant advance in persuasion since radio was invented in the 1890s.

Video: BJ Fogg discusses Simplicity

November 22nd, 2010In this video BJ Fogg discusses the six resources in his model of simplicity. They include: time, money, physical effort, brain cycles, social deviance and non-routine. Simplicity is a function of the scarcest resource at that moment.

(we’re trying to get the embed code to work properly — for now, we’re linking out to Vimeo for you to see the video)

Mobile Health

November 21st, 2010 The Persuasive Tech Lab looks at how mobile phones can be platforms for persuasion. In particular we are interested in how mobile devices can be used to improve the health of everyday people. We focus on what is really working to change people’s health behaviors, right now.

The Persuasive Tech Lab looks at how mobile phones can be platforms for persuasion. In particular we are interested in how mobile devices can be used to improve the health of everyday people. We focus on what is really working to change people’s health behaviors, right now.

Since 2007 we have been bringing together academics, government agencies, mobile vendors, and other private sector health organizations at conferences and workshops to share insights, resources, and best practices.

Mobile Persuasion was the beginning

Early in 2007 our lab organized the first Mobile Persuasion conference. We sold out the event. We then put together a book entitled Mobile Persuasion: 20 Perspectives on the Future of Behavior Change. This book has short, insightful chapters from over 20 authors.

Texting 4 Health came next

Extending our work on mobile persuasion, the lab also created and hosted an event with sponsorship from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, called “Texting 4 Health” in 2008. This was the first-ever conference about using SMS to promote health behavior. Again, we created an edited volume: Texting 4 Health: A Simple, Powerful Way to Change Lives. This book brings together the best ideas about texting and health in 15 easy-to-read chapters.

Mobile Health 2010 emphasized changing health behaviors

In 2010, we put on Mobile Health 2010: Using Mobile Technology to Change Health Behaviors with our co-hosts, Centers for Disease Control and AIDS.gov. Our intent was to feature the best insights into using mobile technology to improve health behavior. You can view presentations from the first day and the second day.

In 2010, we put on Mobile Health 2010: Using Mobile Technology to Change Health Behaviors with our co-hosts, Centers for Disease Control and AIDS.gov. Our intent was to feature the best insights into using mobile technology to improve health behavior. You can view presentations from the first day and the second day.

Mobile Health 2011 was about what really works

In 2011, the Persuasive Tech Lab and CDC hosted Mobile Health 2011: What Really Works at Stanford University. With this event we brought together 400 people from grass roots and national health organizations, academics and mobile vendors for insights and sharing best practices.

Mobile Health 2012 — Let’s take baby steps for big change

In May 2012, the Persuasive Tech Lab hosted Mobile Health 2012: Baby Steps for Big Change. We took a slightly different angle in 2012. Why? Because this method — rapid baby steps — leads to success in three areas: behavior change, collaborations, and experience design. We realized that “baby steps” is an odd focus for an entire event. But we thought it was absolutely the right focus for 2012. The chronic problems in behavior change, collaborations, and product development have a common solution for innovators in Mobile health — and that solution is baby steps.

In May 2012, the Persuasive Tech Lab hosted Mobile Health 2012: Baby Steps for Big Change. We took a slightly different angle in 2012. Why? Because this method — rapid baby steps — leads to success in three areas: behavior change, collaborations, and experience design. We realized that “baby steps” is an odd focus for an entire event. But we thought it was absolutely the right focus for 2012. The chronic problems in behavior change, collaborations, and product development have a common solution for innovators in Mobile health — and that solution is baby steps.

Events for 2013

In 2013 the Persuasive Tech Lab will be holding several smaller events instead of one large one. We’ll focus on elements of health and behavior design. To sign up for updates on our 2013 events, email us.

Mobile Health Project Team

The following people have contributed their time and energy to this project.

- BJ Fogg

- Dave Miller

- Jordy Mont-Reynaud

- Tanna Drapkin

- Stephanie Habif

- Kara Chanasyk

- Kendra Markle

- Dean Eckles

- Adam Tolnay

CaptologyTV

November 20th, 2010Stanford captology students created over 150 short videos to demonstrate how captology works online. The clips at CaptologyTV showed how web services, such as LinkedIn and Facebook, are designed to motivate and persuade users. The videos we placed at CaptologyTV showed how persuasive technology works in popular web sites.

As we created CaptologyTV, we starting seeing patterns of persuasion in the examples. So we dug deeper and synthesized a framework for online persuasion. Our lab published a peer-reviewed paper that summarizes the patterns of persuasion used by virtually every successful Web 2.0 company. We call this process the “Behavior Chain.”

Please note that the CaptologyTV domain is no longer in use by the Persuasive Tech Lab.